From Chapter 11, Learning Difficulties

The message was plain. We were being asked to believe that large numbers of children in the U.S., when they looked at a book, saw something like the photo in the ad, and so, could not read it. Also, that this organization could and would do something about this—it was not clear just what—if we gave it enough support.

I looked again at the children's book in the photo. I found that I could read it without much trouble. Of course, I had two advantages over this mythical "Johnny": I could already read, and I already knew the story. I read it a bit more slowly than I ordinarily would: now and then I had to puzzle out a word, one letter at a time. But it was not hard to do.

This was by no means the first time I had heard the theory that certain children have trouble learning to read because something inside their skins or skulls, a kind of Maxwell's Demon ( a phrase borrowed from physics) of the nervous system, every so often flipped letters upside down or backwards, or changed their order. I had never taken any stock in this theory. It failed the first two tests of any scientific theory: (1) that it be plausible on its face; (2) that it be the most obvious or likely explanation of the facts. This theory seemed and still seems totally implausible, for many more reasons than I will go into here. And there are much simpler and more likely explanations of the facts.

The facts that this theory set out to account for are only these: certain children, usually just learning to read and write, when asked to write down certain letters or words, wrote some letters backwards, or reversed the order of two or more letters in a word, or spelled entire words backwards- though it is important to note that most children who spell words backwards do not at the same time reverse all the individual letters.

I was too busy with other work to take time to think how to prove that this theory was wrong. But for a while I taught in a school right next door to what was then supposed to be one of the best schools for "learning disability" (hereafter LD) children in New England. I began to note that in that particular learning hospital no one was ever cured. Children went in not knowing how to read, and came out years later still not knowing. No one seemed at all upset by this. Apparently this school was felt to be "the best" because it had better answers than anyone else to the question, "Once you have decided that certain children can't learn to read, what do you do with them all day in a place which calls itself a school?" Later, when I was working full-time lecturing to groups about educational change, I had other contacts with other LD believers and experts. The more I saw and heard of them, the less I believed in them. But I was still too busy to spend much time arguing with them or even thinking about them.

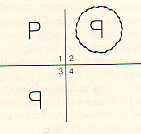

Then one morning in Boston, as I was walking across the Public Gardens toward my office, my subconscious mind asked me a question. First it said, "The LD people say that these children draw letters, say, a P, backwards because when they look at the correct P they *see* it backwards. Let's put all this in a diagram.

Then came the $64 question.

"Now, what does the child see when he looks a the backwards P in space #3, the P that he has drawn?"

I stopped dead in my tracks. I believe I said out loud, "Well, I'll be d----!" For obviously, if his mind reverses all the shapes he looks at, the child, when he looks at the backwards P in space #3, will see a correct P!

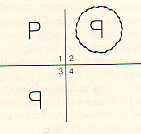

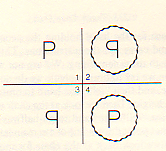

So our diagram would wind up looking like this:

So the "perceptual handicap," "he draws-backwards-because-he-sees-backwards" theory goes down the drain. It does not explain what it was invented to explain. Nor does it explain anything else- this event, the child drawing the letters backwards, is all the evidence that supports it. Why then does this obviously false theory persist? Because, for many reasons, it is very convenient to many people- to parents, to teachers, to schools, to LD experts and the giant industry that has grown up around them- sometimes even to the children. The theory may not help anyone learn to read, but it keeps a lot of people busy, makes a lot of people richer, and makes almost everyone feel better. Theories that do all that are not easy to get rid of.

But then, why does the child draw the P backwards? If he is not, as I have shown, reproducing the shape that he perceives, what is he doing?

The answer is plain enough to anyone who has watched little children when they first start making letters. Slowly, hesitantly, and clumsily, they try to turn what they see into a "program," a set of instructions for the hand holding the pencil, and then try to make the hand carry out the instruction. This is what we all do when we try to draw something. We are not walking copying machines. When we try to draw a chair, we do not "copy" it. We look at it awhile, and then "tell" our hand to draw, say, a vertical line of a certain height. Then we look back at the chair for more instructions. If, like trained artists, we are good at turning what we see into instructions for our hand, we will produce a good likeness of the chair. If, like most of us, we are not good at it, we will not.

In the same way, the child looks at the P. He sees there is a line in it that goes up and down. He looks at the paper and tells his hand, "Draw an up and down line," then draws it. He looks back at the P, then tells his hand to go to the top of the up and down line and then draw a line out to the side. This done, he looks back at the P, and sees that the line going out to the side curves down and around after a while and then goes back in until it hits the up and down line again. He tells his hand to do that. As you can tell watching a little child do this, it may take him two or three tries to get his pencil all the way around the curve. Sometimes the curve will reverse direction in the middle, and that will have to be fixed up. Eventually he gets his line back to the up and down line.

At this point, most children will compare the two P's, the one they looked at and the one they made. Many of them, if they drew their P backward, may see right away that it is backwards, doesn't look quite the same, is pointing the wrong way- however they may express this in their minds. Other children may be vaguely aware that the shapes are not pointing the same way, but will see this as a difference that doesn't make any difference, just as for my bank the differences between one of my signatures and another are differences that don't make any difference.

In thinking that this difference doesn't make any difference, the children are being perfectly sensible. After all, they have been looking at pictures of objects, people, animals, etc., for some time. They know that a picture of a dog is a picture of a dog, whether the dog is facing right or left. They also understand, without words, that the image on the page, the picture of dog, cat, bicycle, cup, spoon, etc., stands for an object that can be moved, turned around, looked at from different angles. It is therefore perfectly reasonable for children to think of the picture of a P on the page as standing for a P- shaped object with an existence of its own, an object which could be picked up, turned around, turned upside down, etc. Perhaps not all children feel this equally strongly. But for those who do, to be told that a "backwards" P that they have drawn is "wrong," or that it isn't a P at all, must be very confusing and even frightening. If you can draw a horse, or dog, or cat or car pointing any way you want, why can't you draw a P or B or E any way you want? Why is it "right" to draw a dog facing toward the left, but "wrong" to draw a P facing that way?

What we should do then, is be very careful never to use the words "right" and "wrong" in these reversal situations. If we ask a child to draw a P, and he draws a T, we could say,"No, that's not a P, that's a T." But if we ask him to draw a P, and he draws one pointing to the left, would should say, "Yes, that's a P, but when we draw a picture of a P we always draw it pointing this way. It isn't like a dog or a cat, that we can draw pointing either way." Naturally, there's no need to give this little speech to children who never draw letters backwards. Indeed the chances are very good that children who start off drawing certain letters backwards would, as with errors in their speech, eventually notice that difference between their P's and ours and correct it, if we didn't make such a fuss about it. But if we are fainthearted and feel we have to say something about backward P's, it ought to be something like the above.

However, I strongly suspect that most children who often reverse letters do not in fact compare shapes. Like so may of the children I have known and taught, they are anxious, rule-bound, always in a panicky search for what the grownups want. What they do is turn the P they are looking at into a set of instructions, memorize the instructions, and then compare the P they have drawn against the instructions. "Did I do it right? Yes, there's the line going up and down, and there's the line going out sideways from the top, and there it's curving around and there it's coming back into the up-and-down line again. I obeyed the rules and did it right, so it must be right."

Or perhaps they may try to compare shapes but are too anxious to see them clearly. Or perhaps, as with anxious people, by the time they have shifted their eyes from the original P to the P they have drawn, they have forgotten the original P, or dare not trust the memory of it that they have. This feeling of suddenly not being able to trust one's own memory is common enough, and above all when one is anxious. Now and then I find myself looking up a phone number two or three times in a row, because each time I start do dial the number I have the panicky thought, "Did I remember it right?" Usually I can only break out of this foolish cycle by saying to myself, "Right or wrong, dial it anyway." It usually turns out to be right. But I can understand how a certain kind of self-distrusting person (by no means rare) might go through this process a great many times. I am sure that many of the failing students I have taught have had somewhere in their minds the permanent thought, "If I think of it, it must be wrong."

It is possible, too, that a child, making up a set of instructions for his hand, might try to use the ideas of Right and Left, but with some of the confusions I will talk about later in this chapter, so that "right" when he was looking at the P might mean the opposite of "right" when he was drawing it. The fact remains that whatever may be children's reasons for drawing letters backwards, there is no reason whatever to believe that seeing them backwards is one of them.

Back to Teach Your Own, or on to Right and Left, from Chapter 11.